Shoot Crates

Table of Contents:

1. Project Requirements

2. Level/Mechanic Design

3. Puzzlescript Programming

4. Unity Port Programming

5. Publishing and Ads

Playable Links:

Google Playstore

itch.io for Windows

Original Puzzlescript

Completion Time:

Design + Puzzlescript: 2 weeks

Unity Port: 2 weeks

Ads + Publishing: 2 weeks

Group Size:

Solo Project

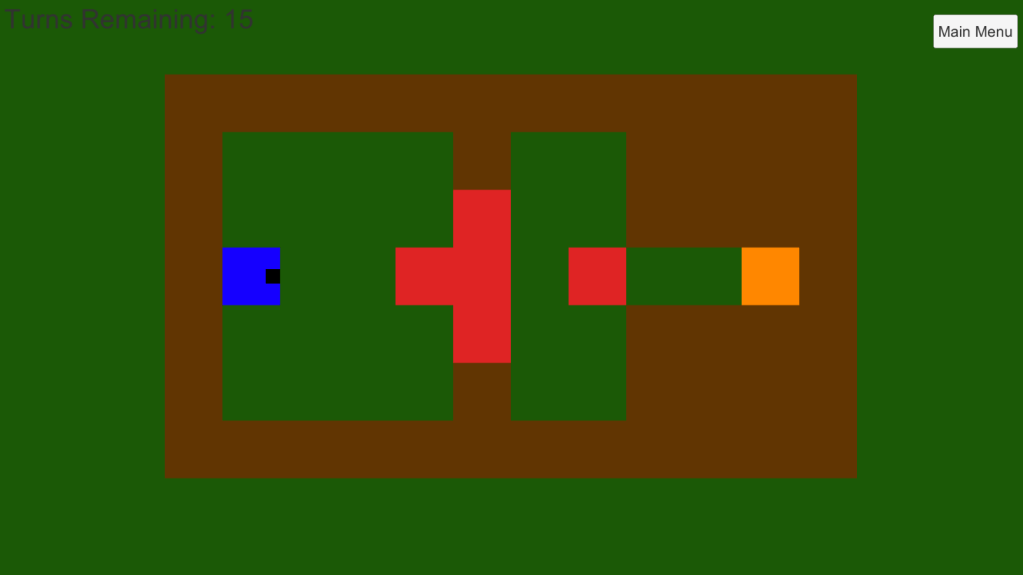

Shoot Crates is a block pushing inversion game. Normally, the player would be tasked with getting a certain number of blocks into the correct position. In Shoot Crates, the player must instead destroy the blocks by shooting bullets out of the player. The goal is to shoot all the orange squares within the turn limit. The player can both move themselves and blocks they touch, as well as shoot bullets that destroy some blocks, pass over others, and do nothing to the rest.

1. Project Requirements

The original project requirements came from my senior capstone class. The main ones were to have

- three different main puzzle mechanics

- only one solution available

- the mechanics mainly be explained through and during gameplay

Finally, it had to be made on Puzzlescript, an open source website for push-block puzzles. Even though I did eventually move this game over to Unity, it was originally a design exercise instead of a programming exercise. Puzzlescript was a good way to make a game with minimal amounts of programming work so we could focus on the design aspect of the game.

2. Level/Mechanic Design

The second requirement had an issue with my main mechanic of shooting blocks. Original block push games have one solution, in the sense that there is only one gameplay position that is a successful completion of the level. Different blocks could be in the different goal spots, but those are considered the same solution because they require the same transformations of the original position.

In order for destruction of the blocks to be the level requirement, I would need another way of limiting the player’s choices to a single solution in each level. The mechanic I created was the use of a turn limit (called a ‘timer’) which restricts the player to the most optimal path. All other paths are not a solution because the player will run out of turns, making only one solution.

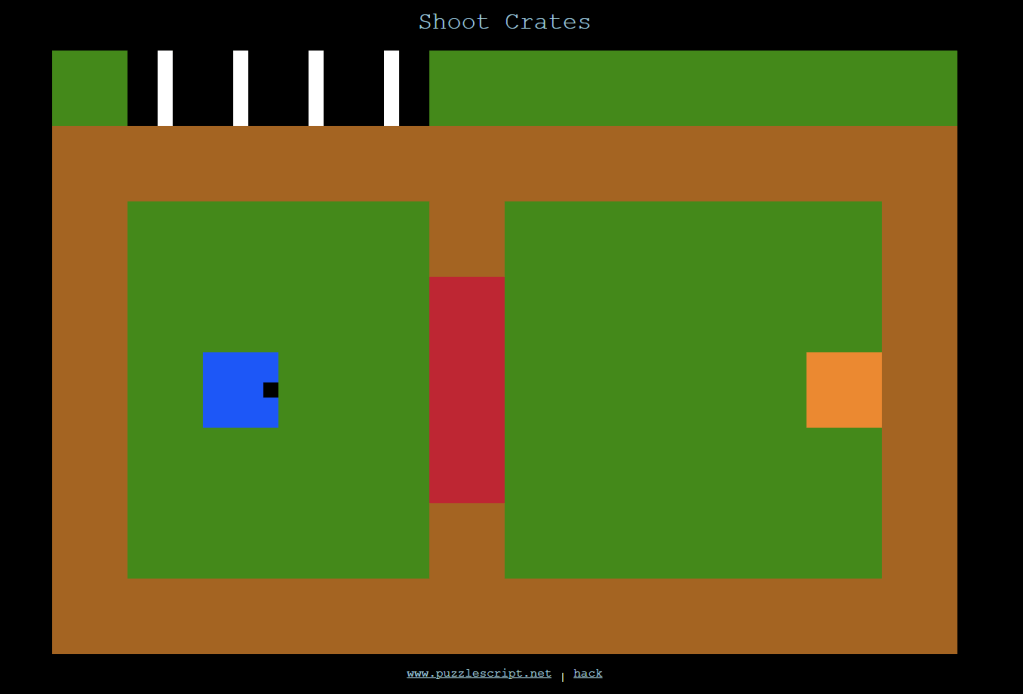

Puzzlescript’s limits as a purely block calculator means that the turn limit is a binary clock at the top of the screen (which is why I call it a timer).

These two mechanics, the turn limit and shooting the crates to win, are the core of Shoot Crates.

The other basic blocks are red and brown. Red blocks are very similar to the orange ones which are the goal, but cannot be destroyed. They are an obstacle to push out of the way. The brown blocks are walls that cannot be changed in any way.

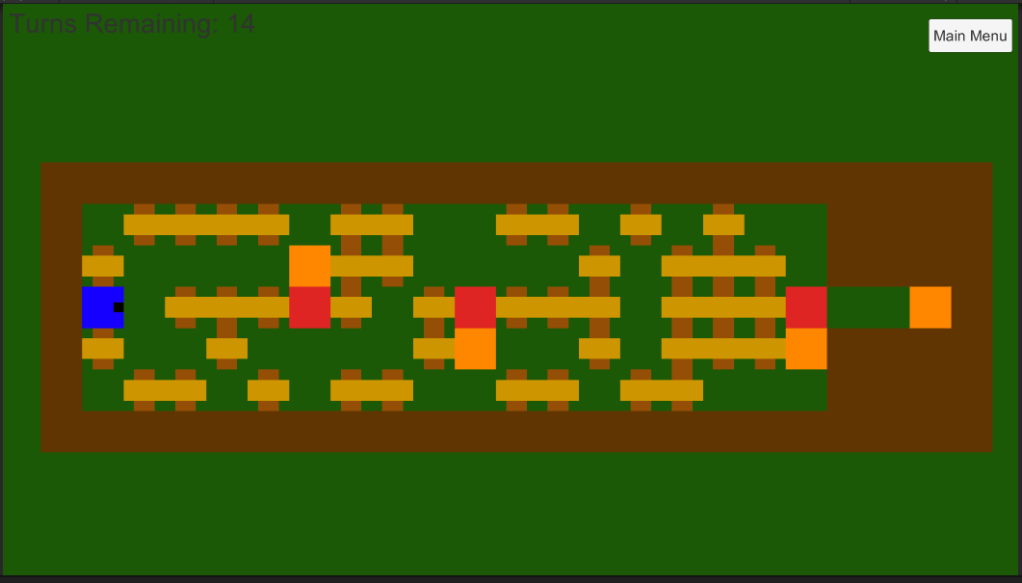

The next main mechanic is the bridge, which warps the distance between points.

Here, many bridges are used to create varying length bridges. When moving into a bridge, the player is transported instantly to the other side of all adjacent bridges, vastly increasing the player’s speed.

This mechanic would be almost useless in a classic block pusher, but because there is a turn limit, they become a critical part of the map. They are both walls to blocks and a highway to the player. This level leverages this mechanic by having the player shoot a bullet, and then running ahead of it to get the blocks into position for the bullet to hit them.

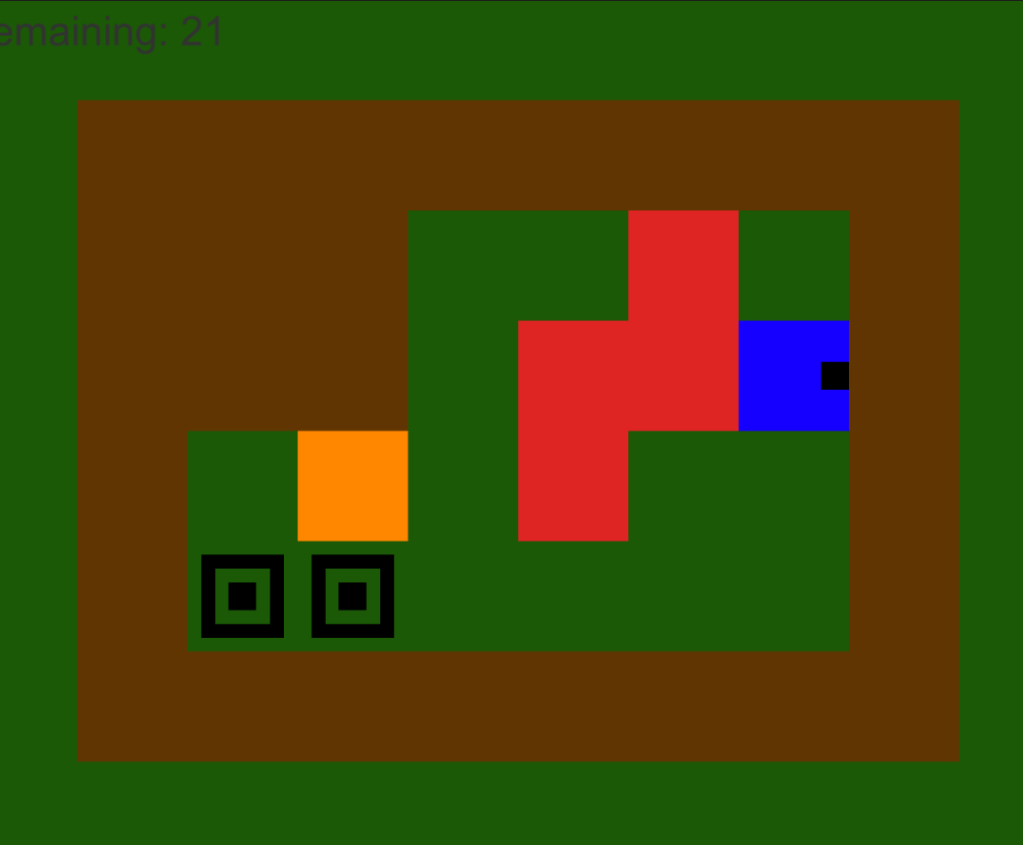

The final mechanic is the pit, a hole in the ground which can break a block pushed onto it once before being filled.

The pit adds a new dimension to the game that ties into how the player can only shoot to the right.

The pit can break blocks when the player is going backwards, highlighting how the original mechanic of shooting is a very asymmetric mechanic. The earlier levels tend to always be going left to right. The pits add in a new idea of going both right to left and breaking the red blocks which, up to this point, were unbreakable.

3. Puzzlescript Programming

Puzzlescript is a language that can only use rules to change things. An example of a rule in Shoot Crates is [ > Player | Block ] -> [ > Player | > Block ], which means when a player moves into a block, move the block and the player one over in that direction. This is why the turn timer is a binary clock, because that is all Puzzlescript could handle. My levels would need to be changed slightly to adhere to a power of 2 number of turns, which is why many have extra squares at the end for no apparent reason.

Another example would be the timer. The goal is to have each move the player makes lead to a 1 moving to the right or becoming a 0 if it cannot move to the right. However, because puzzle script executes all rules equally, the game will try to move a 1, turn it into a 0, and kill the player instantly all at once. To solve this problem, they must be assigned to the same rule group such that only one will be executed a turn, in the priority order provided.

4. Unity Programming

Unity is a language that I have much more proficiency in and is generally more useful, so programming in all of the main mechanics is straightforward. A turn counter, a 2D array of a class that can hold all the information needed, and the same rules from Puzzlescript create the game rather quickly based upon the Puzzlescript engine.

I instead spent my time in Unity in creating a much better way to edit levels in the engine. Puzzlescript uses a text file that the user puts in lines of text where a different character stands for a different block in that square. This is inconvenient to edit, parse, or create with, something which was continually frustrating when making the game originally.

The solution I implemented was to create the 2D array of the level from the objects already in the scene whenever the level is loaded. Each object in the game has a prefab stored which can simply be dragged into roughly the correct position in the scene, and it will be loaded into the level array based upon its tag. Objects are then aligned to the grid (in case slightly misplaced) and the player gains control. This allows for me to create new levels by dragging objects into place, and edit by moving the pieces literally.

5. Publishing and Ads

I decided to use Google AdMob for this project. I planned to publish on the Google Playstore, so to keep things well organized, I wanted to only use first-party Google software.

The first party tutorials on the AdMob quickstart guide were useful, but also slightly out of date. Many of the function calls in the specific ads ended up being incorrectly named, leading me to reading the header files of the Google Ads SDK instead.

The ad type I ended up using was a banner ad on the title screen. I did not want to have any ads get in the way of the gameplay experience, so I placed it at the bottom of the title screen. I also changed my settings in the AdMob policy area to disable 18+ games, gambling games, and other such ads, because many of my playtesters are family friends.

Finally, I created a privacy policy and uploaded on the app store. This app does not create nor store any user data outside of the Google AdMob service, so it is rather simple.

This step took a couple of weeks to figure out, with me being careful to make my privacy policy adhere to many requirements the first time. Further apps that I want to publish and use ads on will naturally take much less time to sort out.